The Japanese New Year & Mochi

The Japanese New Year & Mochi

Today, there are different methods of mochi preparation, which vary from region to region, as well complexity ranging from traditional, multi-person production, to easier modern home production techniques. The diversity is further mirrored in all the ways mochi can be cooked and paired with flavors.

Let’s explore the world of mochi and its special time of year:

Mochi’s significance in Japan

Mochi is, of course, a year-round treat. But seasonally, it carries deeper cultural meanings. Particularly during certain festivals, mochi is strongly associated with good fortune and prosperity.

This is especially true for the New Year, also known as Oshogatsu (or Shogatsu).

Mochitsuki: Making mochi for New Year’s

Leading up to New Year’s in Japan, you might come across mochitsuki — alternatively transliterated as mochi-tsuki — the traditional practice of pounding glutinous rice to make mochi.

While the practice isn’t as ubiquitous as in past generations due to industrially produced mochi being widely available, the tradition continues in many communities especially at the end of the year. It brings people together to pound steamed glutinous rice with large wooden mallets in a mortar-like container, with participants occasionally sparkling water between swings.

Given that this is by necessity a communal, physically demanding effort, the end-of-year mochitsuki has come to symbolize collectivism, unity, and working together to help make a prosperous community. Once prepared, mochi is traditionally eaten around New Year’s celebrations to further symbolize prosperity, good fortune and longevity.

Mochi as a Shogatsu offering and symbolic item

Another New Year’s tradition centered around mochi is kagami mochi. Kagami mochi is made of two round stacked mochi cakes (the bottom slightly larger than the top), topped with a Japanese bitter orange called daidai. These are placed on altars at home as an offering to deities, symbolizing harmony and the continuity of life. The daidai, in particular, is representative of the family through the generations.

After the New Year’s celebrations — traditionally January 11th — the family breaks and eats the kagami mochi in a ritual known as kagami biraki. By then, the mochi has dried out and hardened, so must be broken by hand or with a hammer — not cut! — in a practice that was originally associated with the samurai. From the samurai to modern families, now kagami biraki is an integral part of the ending of Japanese Shogatsu.

Other New Year’s mochi dishes

In addition to kagami mochi, other mochi dishes are enjoyed with Shogatsu.

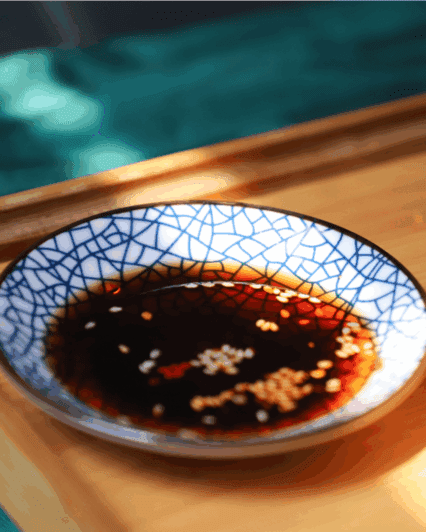

This includes ozoni, a mochi soup that’s hearty and warming for the time of year, which is one of the most common dishes associated with Shogatsu. Its ingredients and flavors vary regionally and by household – some versions will have just a simple dashi broth, while other broths will include miso and other ingredients. As an example, this ozoni recipe from Just One Cookbook’s Namiko Chen is more aligned with the eastern Japanese style of clearer broth, and includes mochi, chicken, Japanese parsley, and komatsuma or spinach.

Other Shogatsu dishes include zenzai and shiruko, sweet red bean dessert soups or stews topped with mochi. These dishes are popular not only during New Year’s but throughout the winter. Both are made with azuki sweet red beans and topped with mochi, which partially melts in the warm soup, creating a delightful contrast in texture. In either case, the mochi partially melts in the warm soup, creating a delightful texture contrast.

Zenzai is typically a thicker version of shiruko, though the distinction can vary depending on the region in Japan. There is significant variety between zenzai and shiruko across the country—some are more porridge-like, while others are soupier. The mochi can also vary, being runnier, grilled, or prepared in other ways, adding further diversity to these comforting dishes.

In the end, mochi is not just a tasty part of New Year’s, but an enduring tradition symbolic of so many values and wishes for individuals, households, families, and whole communities. While modern, industrial mochi production is an increasing part of the Shogatsu celebration, the beloved traditional methods are still lovingly preserved throughout the country.

And regardless of whether you buy mochi at the store or participate in a communal mochitsuki gathering, hopefully mochi brings you a bit of good fortune this year!