What’s the Difference Between Tsuyu and Dashi?

What’s the Difference Between Tsuyu and Dashi?

Dashi and tsuyu are two ubiquitous components of Japanese cuisine. Both are foundational, imparting soups, grilled foods, fried foods, hot pots, noodles, and more with that crucial umami taste without which Japanese cooking would be unrecognizable.

Here’s a quick rundown on both dashi and tsuyu — let’s start with dashi:

Dashi

Although we think of dashi often as just a broth, it’s actually the basis of so many flavors in Japanese cuisine. This simple stock is the base not only for soup dishes like miso soup and ramen, but other cooked foods like okonomiyaki (savory Japanese pancakes), whose batter traditionally uses dashi stock as the liquid.

It is, simply put, synonymous with umami flavor. It’s extremely complex and rich but not overpowering, making it the perfect backbone of so many dishes.

Just like all broths, dashi is made by steeping and simmering anywhere from one to a few different ingredients in water. What’s great about dashi is you can customize it to your own flavor profile. There are several varieties of dashi. Here are some of the most common:

- Kombu dashi – made from kombu (dried kelp)

- Katsuo dashi – made from katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes)

- Awase dashi – made from kombu and katsuobushi

- Iriko dashi – made from dried anchovies or sardines

- Shiitake dashi – made from dried shiitake mushrooms

While simple to make at home, many Japanese households today choose to use instant dashi or granules that can be found at Uwajimaya.

Now, on to tsuyu!

Tsuyu

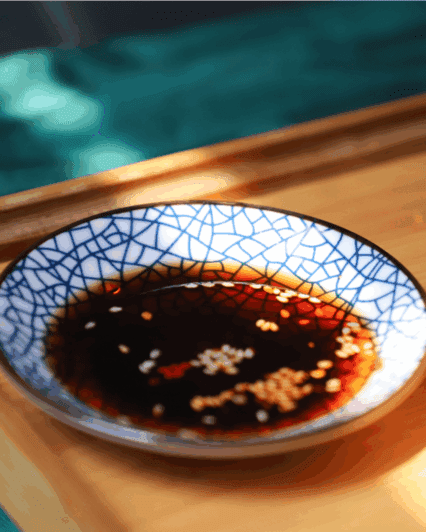

Tsuyu (also known as mentsuyu) is a multipurpose Japanese sauce that can be used as a soup base or dipping sauce and served hot or cold. The first thing you’ll notice about the description of tsuyu is that the liquid base is more complicated than with dashi. Whereas dashi is ingredients simmered in water, the liquid component of tsuyu is soy sauce, sake, and mirin rice wine.

In fact, you could describe tsuyu as dashi plus those three ingredients, although sometimes cooks will add other ingredients as well depending on their intentions and preferences.

With that in mind, it makes sense that the two are united by being flavored with kombu and katsuobushi. Because of this one key difference and one key similarity, you’ll find they’re clearly distinct from each other while also maintaining the same underlying umami tone. But before we get ahead of ourselves, back to the characteristics of tsuyu!

Tsuyu is usually found in two forms: straight and concentrated. Straight type tsuyu does not require dilution. Concentrated type tsuyu requires dilution with water. Depending on the dish, the exact ratio will vary.

In addition to noodle soups, tsuyu is also used as a dipping sauce for tempura, a key ingredient in making tamagoyaki and donburi rice bowl dishes.

Now that we’ve talked a bit about how it’s made and what it’s used for, let’s examine the qualities that differentiate the two.

The distinguishing qualities of Dashi versus Tsuyu

While both of these broths are umami rich and have foundations that give them similar underlying flavors, as we mentioned above the difference in base liquid makes them noticeably different.

The earthiness is more prominent in dashi which, despite having just as much complexity, is a bit more mellow than tsuyu. Dashi has a more rounded flavor — it’s kind of like a bass clef to a soup, batter, or other dish.

Tsuyu, meanwhile, has a bit more acidity. Even though the backbone of tsuyu is a similar earthiness as dashi, it has a bit of tang and is a little more assertive. This is a main difference coming from the inclusion of soy sauce, mirin, and sake. All of these contribute to a very mild but noticeable tartness that’s not present in dashi.

The pungency of flavor is also reflected visually in tsuyu, as it’s generally darker and richer in appearance.

If dashi is more of a base line to other foods, tsuyu can stand out a bit more. It’s not that tsuyu adds more flavor necessarily, just that sometimes with dashi you won’t even realize you’re tasting it — just that whatever you’re eating is extremely delicious and full of umami. And, crucially, that food would taste vastly different and less flavorful without dashi.

Tsuyu and dashi are both super tasty and complex. They both define their dishes but don’t overpower other components, whether meat, vegetables, eggs, or otherwise. The end result is two delicious, versatile ingredients that open up an array of culinary options and flavor combinations. Enjoy!